Concert Schedule Our Catalog MP3s Publicity Materials Songwriting Tutorial Send Us Mail

Excerpted from Chapter 7. of the book, "The Code"

Bitten by the Bug

1958

In the fall, I volunteered to

help decorate the goal posts at

Waiting for their practice

session to begin, the three of them huddled arm in arm and sang pretty good

three part harmony on a song I had vaguely heard on the popular radio of that

time. It was "Tom Dooley," the wonderful

song brought out of the

The Kingston Trio learned it

from that collection and put it on their first album. In the fall of 1958 it was high on the pop

charts and eventually sold more than three million copies. I was so impressed that the three college

football players were so impressed with the song that they had mastered the

harmony parts and sang it with such a mixture of the irrepressible and the

timeless. There was something speaking

to them and to me from the ages.

Cindy recently showed me an

article with a letter that Frank Proffitt had written

to the Warners in 1958. "I got a television set for the kids. One night I was a-sitting looking at some

foolishness when three fellers stepped out with guitar and banjer

and went to singing Tom Dooly and they clowned and hipswinged. I began

to feel sorty sick, like I'd lost a loved one. Tears came to my eyes, yes. I went out and balled on the Ridge, looking

toward old Wilkes,

And in a subsequent letter,

"Then Frank Warner wrote, he tells me that some way our song got picked

up. The shock was over. I went back to my work. I begin to see the world was bigger than our

mountains of Wilkes and Watauga. Folks was brothers,

they all liked the plain ways. I begin

to pity them that hadn't dozed on the hearthstone. . . Life was sharing the different thinking, the

different ways. I looked in the mirror

of my heart - You haint a boy no longer. Give folks like Frank Warner all you

got. Quit thinking of Ridge to Ridge,

think ocean to ocean."

Many groups like the Weavers,

and single artists like Harry Bellefonte and Burl Ives, had released recordings

of songs from the obscure communities of the mountains, but because of their

visibility in the popular media many people credit the Trio with starting the

great trend which was to become known as the Folk Music Revival. I became a fan of the group. I had their first four albums, and learned

just about all the songs vocally, and when I could get my hands on a

five-string banjo I would learn those parts too.

I was able to borrow a banjo

from a friend, actually the son of a friend of my

mother's who was a year younger than I.

It was a clumsy instrument, a Kay, infamously a very cheap banjo made

mostly of Bakelite. One could tell that

it was an inferior instrument because it had about half the number of brackets

holding the head on. Once I was able to

tell the difference, I wouldn't have wanted to be seen with it.

I continued to practice, and

again, through a friend of my mom's (I hadn't yet come to realize how

supportive she was of my music efforts) I met Bob Jordan. Bob was also just beginning to play the five-string

banjo. He was a couple of years older

and was just going into college at UCLA.

He would come over and show me a few things about the banjo and stay for

dinner.

Eventually I saw an ad for a

five string banjo in the local paper. I

don't know just how I came up with the seventy-five dollars, but I bought it,

and was pleased to find that it was every bit the best banjo I could want. Actually it's more than that. It's a 1921 Bacon Grand Concert. It has beautiful mother of pearl inlay very

tastefully distributed on the ebony fretboard, peghead and butt of the neck. It has the very distinctive tubular resonator

invented by the Bacon people and carried through on many high-end custom banjos

today by Bart Reiter and others. It's

worth many times what I paid for it.

I bought it from a man named

Bill Smith who had a recording studio in

Dave Guard was my hero. I emulated his playing as completely as I

could, although vocally I favored Bob Shane.

Dave was learning the banjo as time went on, and with each new album he

and I grew into the instrument together.

As it turned out, Dave was working with Pete Seeger's

book, "How to Play the Five String Banjo."

So many people have acknowledged that book over the years. I have loved it, and it's still available

from Sing Out Press.

The humor on the "Live at the

Hungry i" album was a revelation to my sheltered fifties sensibilities. Memorized by just about everyone I knew, it

was one of the things that opened those doors into a more

worldly world. It never occurred

to me at the time that even the name of the

Many people credit that

recording with setting in motion their own stagecraft, their style of

presentation, especially the humorous banter leading up to the songs. Years later I had a chance to tell Dave Guard

what an influence he had been, and how much I admired his sense of humor on the

"Hungry i" album. He replied very

modestly that he was only "doing Lou Gottlieb," (the

bass player and professorial spokesman for the Limelighters.

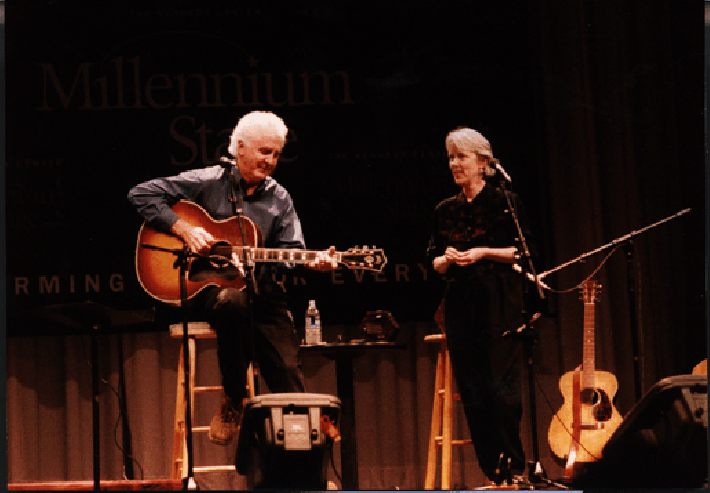

To

view our live concert from the

Millennium Stage of the Kennedy Center

Visit

the Kennedy Center archives.

If you don't already have RealPlayer

you can download it for free from Real.com

![]()

Please send any correspondence or requests for

information to:

Compass Rose Music

Direct your e-mail messages to:

Steve Gillette, gillette.steve@comcast.net

or to:

Cindy Mangsen, cindymangsen@comcast.net

Come back for more information, lots more Folk Music

resources on the Internet,

our concert schedule, and of course, the jokes.